Several weeks ago, I described research at Israel’s Tel-Hai Academic College, which may enable investigators to create a rough portrait of a person from DNA. In the August/September 2012 issue of Forensic Magazine, Timothy D. Kupferschmid provides background information about this type of technology.

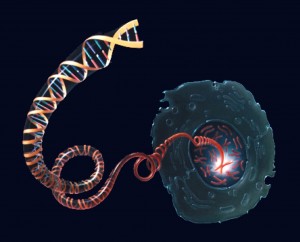

Kupferschmid, executive director of Sorenson Forensics, explains that early attempts at forensic phenotyping (i.e., creating a portrait from DNA) used DNA analysis to determine gender, and to predict hair and eye color. Sorenson Forensics developed a DNA test to predict a person’ genetic ancestry. The test relies upon the observation that, during the course of human history, portions of the DNA of human populations living in geographically isolated regions became slightly distinct from the DNA of human populations in other regions. Certain DNA markers are associated with five populations: Western European, Western Sub-Saharan African, East Asian, Indigenous American, and residents of the Indian Subcontinent. As Kupferschmid emphasizes, the test does not reveal “ethnicity” or “race,” which are social concepts that geneticists consider to be arbitrary and without scientific foundation.

You can find details about this new aid for criminal investigations in Kupferschmid’s article, “Forensic Phenotyping: the 21st Century Composite Sketch.” The investigators of your mystery story will thank you.