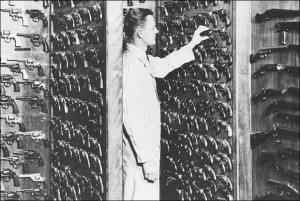

Earlier this month, the FBI posted a story about the agency’s reference firearms collection. Started in 1933, the collection of 7,000 firearms is stored at the FBI Laboratory in Quantico, Virginia.

FBI Lab firearms examiners use the assembly of weapons to study and test firearms in support of current investigations. The library of handguns and rifles includes a database of typical marks made by the weapons, and more than 15,000 types of commercial and military ammunition. Suppressors, magazines, muzzle attachments, grenade launchers and rocket launchers also reside here.

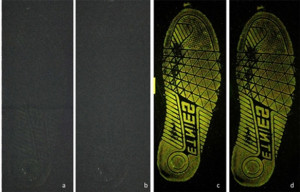

“Oftentimes this collection is used in active cases in comparing known samples from our collection with question samples from the field,” explained FBI firearms examiner John Webb. “Often, an investigator will receive a part of a firearm or a firearm that isn’t functional. We can take that and compare it with our reference collection, determine what isn’t functioning, and repair it so we can obtain the test fires we need to conduct examinations with bullets and cartridge cases.”