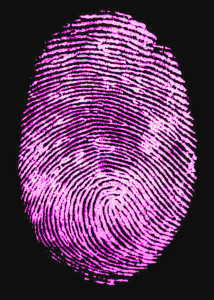

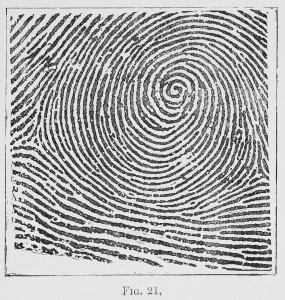

During July, the University of Leicester Press Office posted a report about a new technique for visualizing latent fingerprints from crime scenes. Visualizing usable latent fingerprints poses a challenge; about 10% of crime scene fingerprints have sufficient quality to be used as evidence during a trial.

The new technique exposes fingerprints by using the electrically insulating properties of a fingerprint’s sweat and oil deposits. The chemicals in a fingerprint block an electric current used to deposit a colored, electro-active film. The deposited film collects on the surface between fingerprint deposits to create a negative image of the fingerprint. The technique is very sensitive and can be used in combination with traditional visualization techniques, such as fingerprinting powders.

“By using the insulating properties of the fingerprints to define their unique patterns and improving the visual resolution through these color-controllable films,” said team leader Professor Robert Hillman in a press release, “we can dramatically improve the accuracy of crime scene fingerprint forensics. From the images we have produced so far, we are achieving identification with high confidence using commonly accepted standards.”