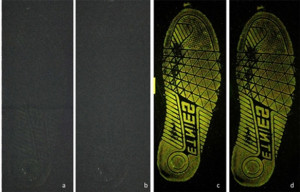

Shoeprint in blood on black nylon before enhancement (a) and after enhancement with three techniques (b, c, and d). Source: University of Abertay Dunde.

Last week, we saw that forensic scientists at the University of Abertay Dunde (Scotland) invented a way to recover latent fingerprints from foods. Late last year, the university’s scientists announced a new method for visualizing latent shoeprints.

Dr. Kevin Farrugia modified traditional fingerprint visualization techniques to develop the first detailed images of latent footwear marks left on fabric. Farrugia explained that a footwear mark can be created with a contaminant on the sole of the footwear and left on carpet, clothes, or a body.

“However, as the marks fade and become less visible,” Farrugia said, “the pattern on the sole of the shoe, by contrast, becomes much clearer and better defined. And it’s these prints – the ones that we can’t actually see – that are the most useful at a crime scene, especially when it isn’t possible to recover other types of evidence such as fingerprints and DNA, because they can tell you things like what size, and even what brand, of shoe the perpetrator was wearing when they committed the crime.”

These general features are class characteristics of the footwear. A print can reveal even more than this.

“[B]ecause everyone walks differently,” Farrugia explained, “the sole of their shoes will have acquired what we call random and individual characteristics that are specific to that shoe and person, which means, when the police have got a suspect, they can get their shoes, and if the shoes match, it can lead to a conviction.”

For the first time, a method can be used to produce a clear, detailed image of a latent footwear print without damaging it. Farrugia’s technique is effective with both new and old prints, and may be used to reinvestigate cold cases.

You can learn more details about this method at the Abertay University website.