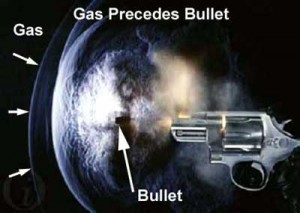

Traditionally, gunshot residue contained gunpowder residues (such as partially-burned or unburned gunpowder) and lead residues. However, an increasing number of ammunition manufacturers produce ammunition that contains little or no lead. This change is good for the environment, but creates a challenge for criminal investigators, because crime labs test for gunshot residue by detecting the presence of lead, barium, and antimony.

During June 2012, forensic researchers at Florida International University announced a new technique that can potentially link a suspect to fired ammunition by identifying the chemical signature of the powder inside a bullet. In this approach, a chemist analyzes the chemical composition of a bullet’s smokeless powder. The method reveals the particular formula of the smokeless powder, which further identifies the manufacturer of the powder.

“Crime labs all over the country are faced with the reality that their only way to analyze whether a gun was fired by a suspect may become obsolete,” said chemistry Professor Bruce McCord in a press release. “Our discovery is not only more accurate, but it can determine the type of gunpowder used in a crime even if the gun is never recovered.”