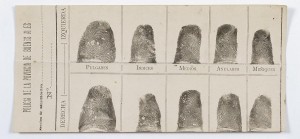

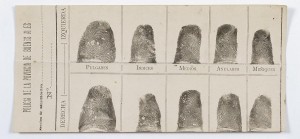

Fingerprint card of Francesca Rojas, 1892. Source: National Library of Medicine.

On the evening of June 19, 1892, Francesca Rojas burst into a neighbor’s shack on the outskirts of Necochea, a small coastal village in the province of Buenos Aires. She cried that Velasquez, a laborer at a nearby ranch, had murdered her children. Velasquez had wanted to marry Rojas, but earlier in the day, she told him that she planned to marry a younger man. According to Rojas, Velasquez became furious and swore revenge.

A search of Rojas’ hut revealed the bodies of a young boy and girl with fatal head wounds. The police arrested Velasquez and questioned him. The farm hand refused to confess, even under torture. Meanwhile, rumors about Rojas began to surface. Gossipers said that a young man had told Rojas that he would marry her if she did not have the two children. Wondering if Rojas might be the murderer, the police sought help from La Plata regional headquarters.

La Plata Police Inspector Eduardo Alvarez reexamined the Rojas hut. He noticed a dark, brownish mark on the door of the children’s bedroom: the imprint of a bloodstained human thumb. Alvarez knew about the value of fingerprints. He borrowed a saw and cut a piece of the door that contained the finger mark. Alvarez returned to La Plata with the evidence and with Rojas in custody.

At the police station, he rolled Rojas’ right thumb on an ink pad, and then pressed it on a sheet of paper. Then, he called in Juan Vucetich, head of the La Plata Bureau of Identification and Statistics. Vucetich had become interested in fingerprints after reading Francis Galton’s book. He performed his own fingerprinting studies and devised a classification scheme. After Vucetich matched Rojas’ inked print with the bloody thumbprint on the door, Rojas admitted to killing her children. The case has been hailed as the earliest murder investigation solved with fingerprints.

With further research, Vucetich perfected his fingerprint identification system and published the details in his book, Dactiloscopía Comparada (1904). The Vucetich system is still used in most Spanish-speaking countries.