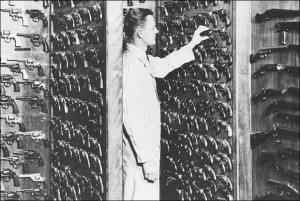

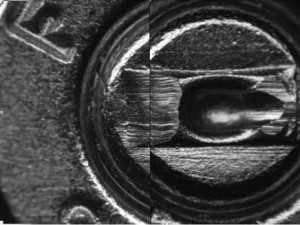

Photo shows two test-fired cartridge cases from the same firearm compared side-by-side with a comparison microscope. Source: Stephen G. Bunch et al., “Is a Match Really a Match? A Primer on the Procedures and Validity of Firearm and Toolmark Identification,” Forensic Science Communications 11(3) (July 2009).

Fourteen years ago the ATF (today, called the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives) set up the National Integrated Ballistic Information Network (NIBIN). US partners of this network use Integrated Ballistic Identification Systems (IBIS) to obtain digital images of marks on fired cartridge cases and bullets. These cases and bullets are either recovered from a crime scene or from a test firing of a suspect weapon. The images are electronically compared with stored NIBIN entries. On TV shows, an electronic match – a hit – often ends the investigation. In real life, a high-confidence electronic match means that a firearms examiner compares original evidence with a microscope to confirm the match. So far, NIBIN partners have confirmed more than 50,000 NIBIN hits.

Last month, KVOA’s Lupita Murillo in Tucson reported a practical problem with NIBIN analysis. Although an electronic comparison may only require hours, somebody has to acquire and upload digital images into the network. The Tucson Police Crime Lab had 1,200 backlogged cases that needed to be entered into the system.