CBC News report on firearm identification technology.

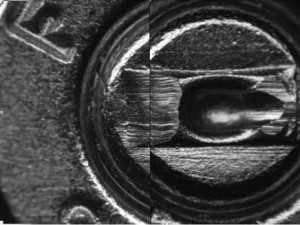

On May 13, CBC News posted an article entitled, “Bullets Decoded: Inside a Toronto Firearm Lab.” As detailed on the CBC News website, Toronto police use the Integrated Ballistics Identification System (IBIS) to analyze three-dimensional marks created on bullets and shell casings upon firing. The technology reveals links among crimes. In one case, for example, the same gun had been fired during two otherwise unrelated shootings and a bank robbery.

Developed by Montreal-based Forensic Technology, IBIS is used by Canadian and US police forces, as well as by other law enforcement agencies throughout the world. According to Robert Walsh, Forensic Technology’s CEO, IBIS has linked guns with more than 100,000 crimes in the United States alone.

IBIS’ success has not gone unnoticed by criminals. “I think the criminals have learned through the court system and word of mouth with each other that IBIS exists and it’s able to link up crimes to other crimes,” Toronto police detective Mike Grierson told CBC News. As a result, criminals sometimes “police their brass,” to avoid leaving evidence at a crime scene.